Carousel 1 sold a series of three 1/43 Watson Roadsters under the Hobby Horse brand. The models produced were the 1960 Indianapolis 500 winner driven by Jim Rathmann, the 1961 winner driven by A.J. Foyt, and the 1962 winner driven by Rodger Ward. These models are excellent candidates for conversions as there are decals available to produce a wide selection of roadsters.

In addition to the obvious differences in paint and graphics, the three original models differ slightly in a few areas.

The 1960 car has a bump on the engine cover, a small fuel filler, a straighter exhaust pipe, and a tall front-mounted oil tank with a filler cap on the front slope of the tank.

The 1961 car has a bump on the engine cover, a small fuel filler, a more angular exhaust pipe, and a tall rear-mounted oil tank with a filler cap on the rear slope of the tank.

The 1962 car has a scoop on the engine cover, a large fuel filler, a straighter exhaust pipe, and a shorter rear-mounted oil tank with a filler cap on the top of the tank. It also has a suspension adjustment rod on the right side that the other cars don't have.

If I have two or more donor cars on hand I mix and match the parts to get the most accurate components on my conversions, but the differences are very subtle so I'm not afraid to take a bit of "artistic license" with the parts if it produces a good result.

The Hobby Horse Watsons are assembled with no screws and there is no obvious way to get them apart. It took a bit of experimentation, but I've got it down to about a 15 minute operation.

The donor car is the Rodger Ward 1962 Indy winner.

The first step in disassembly is removal of the seat. The seat is soft flexible plastic and is glued in place. Sometimes these can be lifted right out with a gentle tug, but more often they require a bit of persuasion. I use a small straight screwdriver and wiggle it under the seat starting on the right side and then moving to the left, working slowly until the seat releases.

I just keep working them gently until they release. I haven't torn one yet. So far so good. Under the seat is the rivet head that holds the body together. More on that later.

The next step is to remove the front wheels. This is simply a matter of grabbing both wheels and rotating them back and forth while pulling them apart. It doesn't take much effort.

The front steering arm/brake assembly is pressed into the right side of the body at the nose and along side the cockpit.

A little wiggle and a gentle tug will typically release the front of the assembly (be careful not to break the steering arm). To release the rear linkage pin I use a small pair of end cutters to lightly grip the linkage, then roll them along the flat edge slightly (like pulling a brad) to coax the pin out of the body.

This takes a bit of finesse and a soft touch, but I haven't broken one yet.

At this point the remaining front suspension parts can be removed. They are usually easy to remove and are sometimes so loose that they fall out on their own.

Since this is the 1962 car it has an additional suspension arm that the other cars lack. It is removed using the same method as the steering linkage. If the conversion won't include this arm it can be snipped off. I prefer to remove them in one piece and put them in my parts bin for later use.

In my experience, the roll bars on these cars almost always break. Fortunately they are easy to replicate using copper rod from the local hobby shop, so I just pull them out and let the chips fall where they may. This one broke on the left side at the mounting point so it would be salvageable, but a copper replacement is easier and stronger. In this case a replacement won't be required because the conversion will be a car from 1958 and won't have a roll bar.

I remove the rear wheels using the same technique as used with the front wheels. They typically come off with a minimum of effort. The metal body will now sit flat on the workbench. If the donor car is the 1960 Rathmann model with the oil tank in the front, I remove the rear suspension at his point (as shown further below). The rear-mounted oil tanks interfere with the removal of the rear suspension. If the conversion involves moving the tank from the rear to the front I remove the tank from the outside by cutting the pins with a hobby knife, then I remove the rear suspension. If I am keeping the rear mounted tank I make the effort to remove the tank intact from the inside and then remove the suspension as I am doing here. It saves work when reattaching the tank later on.

To separate the body from the belly pan I drill through the center of the rivet located under the seat with a 5/64" drill bit. I keep the drill as square and level as possible and drill very slowly.

I drill all the way through the rivet and through the belly pan.

Next I drill off the rivet head using a 5/32" bit. I drill just enough to remove the flange of the rivet and release the body, not all the way through the pan.

Cleaning up the top of the rivet with a small file ensures that the two sections of the body will fit back together correctly.

I put the body back together...

...and check for a good fit.

The screw used for reassembly must sit flush with the floor of the cockpit or the seat won't fit properly. I use a 3mm countersink screw.

The next step is to tap threads in the belly pan. I use a 3mm fine thread tap...

... then screw the body and belly pan together and check the fit.

Next I grind down the screw so it is flush with the belly pan. The screw I used in this example had already been cut down.

If the pedal assembly remained with the belly pan (in this case it didn't) it can be removed by gently prying it loose. The gear shift assembly is glued into two holes in the belly pan. I scrape away the glue and use end cutters to pry up on the pins.

Most of the time these pins break off, sometimes one will release (like this time),

rarely both will release. It's easy to glue this part back in place so

it's no big deal if it breaks off at the pins, but it's worth a try to

get the part out intact.

I've never had any luck removing the steering wheel prior to separating the body. Typically the steering column releases from the pedal assembly during the separation of the body and the belly pan. In this case the pedal assembly stayed attached to the column.

The steering wheel/dashboard/frame assembly is attached to the body with a metal rivet head.

I try to drill the rivet head off as much as possible. Since the assembly is plastic and the rivet head is metal the bit tends to drift. The windshield is fragile so it is important to support the car in such a way as to prevent the windshield from taking the load when drilling the rivet.

Next I remove the steering/dash/frame assembly. Sometimes these will pop right out. Sometimes they require some prying.

If the steering/dash assembly comes out cleanly, I keep it intact for reassembly. If not, I separate the frame rails and trim off the mounting tab from dash. This makes for a better fit later on.

The most fragile part on the Hobby Horse roadsters is the windshield. The clear plastic is thin and a bit brittle. It is attached to the body with two pins and some glue. How much glue varies from car to car. If there is enough of a gap between the body and the screen I try to use a hobby knife with a very thin blade to cut the glue bead prior to removing the windshield. This is a judgement call, as the part won't tolerate much pressure and I don't want to inadvertently cut through the pins. The only method I have found to remove the windshield is by using a spring-loaded center punch to pop the pins loose from the bottom.

I've had two instances (including this one) where the windshield has chipped out slightly at the bottom, but I haven't had a cracked or broken windshield. The bottom edge is easy to repair with a bit of putty, and since it will be painted the repair is invisible when the model is finished.

I use a hobby knife to pry off the fuel filler cap.

Being careful not to let the cap sail away!

The tank should then come off fairly easily. Sometimes I need to push the back of the pins a bit from the inside.

I cut the pin holding the oil cap in place flush to the inside of the tank and gently wiggle a hobby knife blade between the cap and the tank until the cap loosens, then remove the cap by pulling it straight away from the tank.

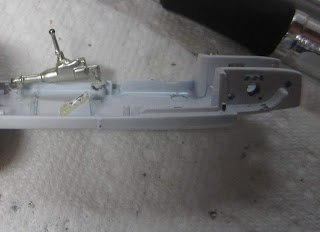

The rear suspension and push bar is molded in one piece. It is delicate but it is fairly flexible. It takes a light touch to remove it in one piece. I use a small pair of diagonal cutting pliers to gently grip the forward-most pin and pry it loose by laying the flat side of the pliers against the body and rolling them back (once again, like pulling a brad). The drive shafts usually release on their own as the front pins are loosened. I work slowly and carefully. As soon as the front pin releases, I switch to the small end-cutter and start to work loose the two rear pins located behind the drive shaft and just above and to the rear of that (on the front of the push bar). It's not uncommon for one or both of the push bar pins to break off (as one did here), but I try not to break the suspension pins. The push bar rests against the body and a broken pin won't be visible. A broken suspension pin will require a bit of fabrication later on.

Once both sides are released it is time to remove the rear push bar pin by sliding the entire assembly rearward. To make sure the suspension pins and drive shafts don't slide back into place during this process I tuck them under the body.

If the conversion is a pre-1960 version I could simply cut the rear pin since your car won't require a push bar. That is what I did here. If I'm going to use a push bar on the model it is worth the effort to try to remove the pin. As with the side push bar pins, the rear of the bar rests against the body so a broken pin isn't a big deal. I'd rather break the pin and tack it in place with a dab of glue at reassembly than break the push bar and have to repair that.

Finally, the exhaust needs to be removed. Once again, gently prying with the end-cutter works for me on the rear exhaust mount.

Once the rear mount is loose, I trim the plastic pins from inside the body. If I'm lucky the exhaust will be loose enough to remove at this point. I'll try pulling it loose but I don't force it. The best method I've come up with to remove the manifold end of the exhaust is to heat the pins from the inside using a fine soldering tip. I start with the rear most manifold pin and then move to the front pin.

It takes a minute or so but the pins will release and will be reusable.

That's it! Now I'm ready to strip the paint and do any required modifications or repairs prior to refinishing.

Your results may vary.

This post is for information purposes only. I take absolutely no responsibility whatsoever for the completeness or accuracy of this post, or for anything that I have ever done, said or written. Why start now?